Mass Violence and Atrocities

Reflections on “Reporting from the Front Lines of Peace”

Through independent reporting and policy dialogue, a partnership with The New Humanitarian dug deep into what works to strengthen resilience and build peace.

What does it look like to build peace in countries and communities affected by violence and conflict? Media attention often follows the trail of violence after conflict already erupts or focuses on peace deals at the level of international diplomacy. But these aspects are only part of the story…

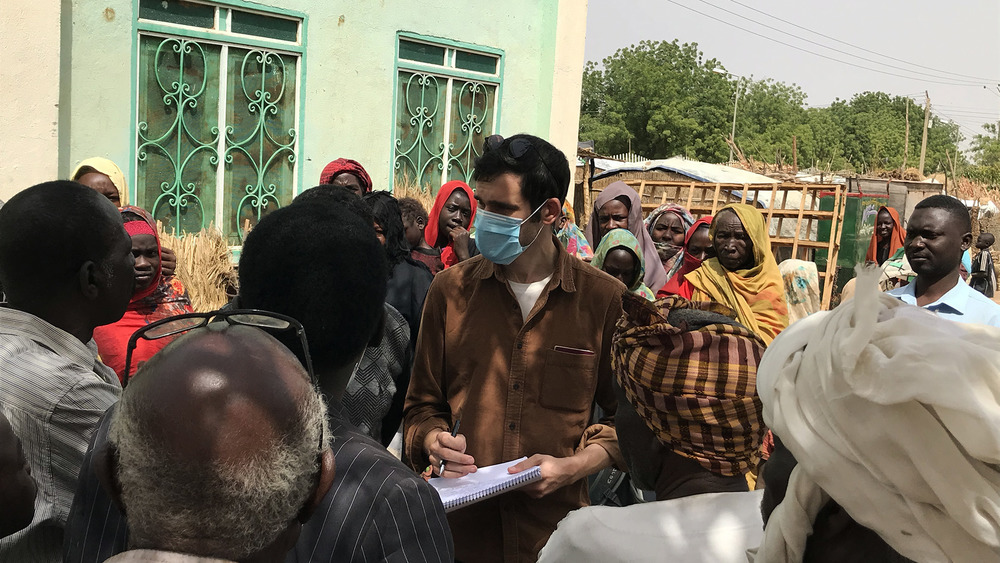

CREDIT: Philip Kleinfeld/TNH

Peace is also built up at the local level, through individual and community-driven action that strengthens resilience in societies over time. While international interventions are sometimes necessary, when peace deals fray or prove ineffective, initiatives by local peacebuilders create opportunities for stemming violence and sowing the seeds of future reconciliation.

Beginning in 2020, The New Humanitarian (TNH) and the Stanley Center for Peace and Security partnered to explore what makes societies resilient to conflict and mass violence. The independent reporting series by TNH, Beyond the Bang-Bang: Reporting from the Front Lines of Peace, investigated peace efforts in various contexts around the world, deeply examining community-level, national, and international actions that aim to prevent violence or contribute to peace—while the Stanley Center drew reporting into policy conversations.

In this series—which includes nearly 50 stories published over two years—TNH reported on the fault lines within and around conventional peace processes. Without structural changes, peace deals can fail to mitigate local violence. For instance, a historic peace deal in 2016 promised to put an end to a half-century of civil war in Colombia. But a militarized approach by the government (one which simultaneously reneged on promises of crop substitution programs) allowed for a resurgence of gang violence, as Joshua Collins reported for TNH.

CREDIT: Luke Duggleby/TNH

Even at the national or provincial level, peace deals can also run aground when local stakeholders are excluded from the process. In northwest Nigeria, where heavily armed and mobile criminal gangs terrorized rural communities, repeated military operations failed to address the root causes of violence at the local level: land disputes and lack of policing. Negotiated peace deals proved ineffective in stopping cycles of violence because they also lacked mechanisms of accountability for criminal leaders and did not put in place a formal program for disarmament, demobilization, and rehabilitation (DRR). Idayat Hassan examined these and other root causes of banditry in northwest Nigeria in her reporting for TNH.

Peace even begins at the most hyper-local level, with the individual. More than a year into the reporting series, TNH’s CEO Heba Aly asked Nobel Laureate and former President of Liberia, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, about what the international community can do to support local peace activists. President Sirleaf’s response is worth listening to (in full below). She laments the opportunities lost when the international community focuses on “controlling a situation in which peace is no longer there” rather than on building resilient communities to prevent the outbreak of violent conflict.

Excerpts from a Q&A with Nobel Laureate Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, following the Kofi Annan Geneva Peace Address, organized by The Graduate Institute, the Kofi Annan Foundation, and the Geneva Peacebuilding Platform as part of Geneva Peace Week (2021).

But what does building peace look like from the ground? A few key themes emerged from TNH’s reporting.

First, hyper-local peace deals can often enable communities to move forward even amid violent conflict happening in the region. In the village of Doka in northwest Nigeria, the Adara and Fulani communities struck a peace deal to end a cycle of tit-for-tat violence that haunted a region too remote for government forces to keep the peace. Séverine Autesserre, author of the book The Frontlines of Peace, described in an interview with TNH how peace is built from the bottom-up around the world in communities like Doka, where national or international efforts have failed to safeguard peace.

Second, women play a crucial role in brokering and sustaining peace. With conflict still simmering in South Sudan, a multi-ethnic Women’s Union formed in the town of Malakal to restore the historical interdependence among now-warring groups. In south Thailand, where high-level peace talks have not resolved a violent insurgency, women became the foundation for ground-level initiatives for peace. Caleb Quinley’s story for TNH on this conflict cites research by Duanghathai Buranajaroenkij, a lecturer on human rights at Mahidol University in Bangkok, on how “women can engage groups and areas that are difficult for other actors to access.”

CREDIT: Sam Mednick/TNH

Third, forgiveness is both extraordinarily powerful in healing divisions, but also a nuanced proposition. Unearthing mass graves in Burundi overseen by a truth and reconciliation commission allowed communities to come to terms with a legacy of violence. In his story for TNH, Désiré Nimubona wrote, “I have seen some remarkable things: family members identifying the remains of their loved ones after decades of searching; killers asking victims for forgiveness.” But in the midst of conflict, programs such as sulhu in Nigeria to rehabilitate senior Boko Haram defectors raise important questions on the line between pragmatic amnesty and unjust impunity, as Obi Anyadike reported for TNH.

The reporting series by The New Humanitarian calls attention to how foundational locally-led peace initiatives are to sustaining peace and building long-term societal resilience. Still, peace is also political. Diplomatic and political solutions at the local, national, or international level are needed to ensure that structural and institutional frameworks for peace are in place. When integrated together, approaches at multiple levels can increase the chances of a lasting peace, while local perspectives are still the most responsive to situations on the ground. Even when peace seems out of reach, envisioning life without violent conflict can foster pathways to peace or open the door to healing and reconciliation.

CREDIT: Steven Grattan/TNH

In regions with a history of religious tolerance and social harmony, bouts of violence can warp perceptions of a peaceful society and unravel the fabric of accord. And no place is immune from these processes if left unchecked. Restoring the frayed bonds among communities requires an understanding of both the risks of mass violence and the factors of societal resilience. (For a perspective on how COVID-19 has affected these processes in various countries, explore our multimedia reporting project, Red Flags or Resilience? COVID-19’s Impact on Atrocity Risks.)

Looking at the full body of work produced as part of this reporting series, there are many lessons and important points of view that can inform policy conversations. From very personal perspectives of those directly impacted by violence and conflict, to those working at all levels to build pathways to peace, rich reporting and views from the ground can shine a light on opportunities for breaking cycles of violence and building lasting peace.

The Stanley Center also produced, in collaboration with The New Humanitarian, a 3-part podcast about the reporting series that was hosted by Mark Leon Goldberg and featured at the Fragility Forum 2022:

![]() Voices from the Ground: Reporting from the Frontlines of Peace

Voices from the Ground: Reporting from the Frontlines of Peace

Episode 1 – Obi Anyadike on reporting for TNH’s series on peacebuilding

Episode 2 – Hassan Idayat on banditry in rural northwest Nigeria

Episode 3 – Désiré Nimubona on exhuming graves in Burundi

Learn more about the partnership between the Stanley Center and The New Humanitarian. Sign up for the TNH peacebuilding newsletter and read all of the stories in the reporting series, Beyond the Bang-Bang: Reporting from the Front Lines of Peace: