Mass Violence and Atrocities

Journalists report the pandemic’s impact on risks and resilience to mass violence around the world

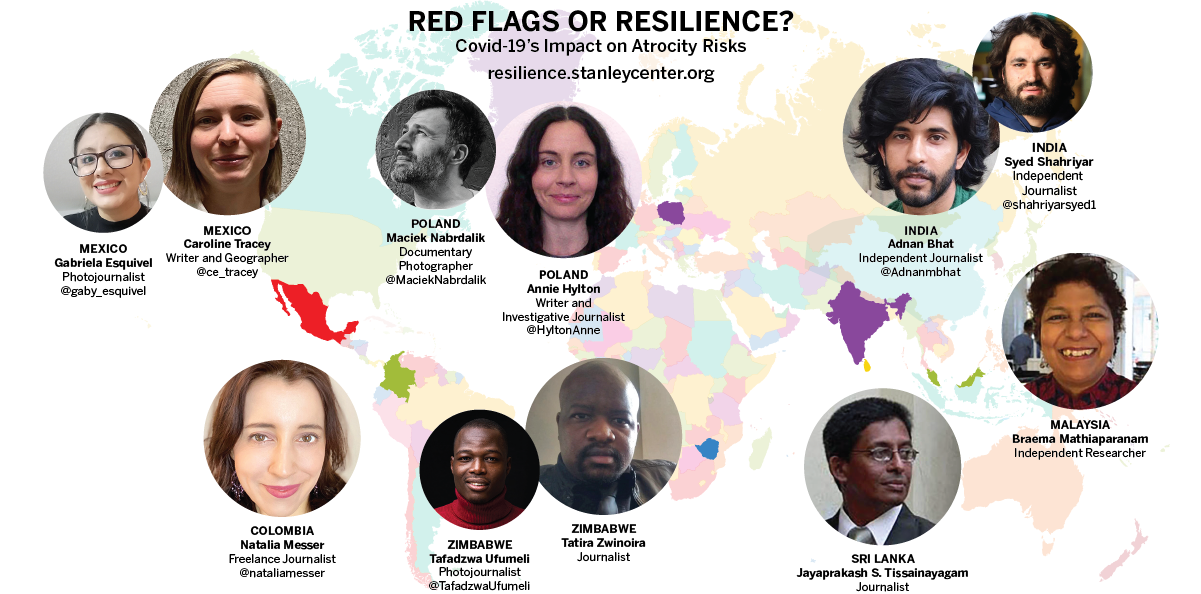

Our multimedia commissioning project investigates stories of atrocity risks and resilience in seven countries across five continents during COVID-19.

At the end of 2020, one year after the start of the deadly coronavirus pandemic, the Stanley Center invited journalists to pitch stories that explored the connections between COVID-19 responses and factors for risk and resilience to mass violence and atrocities around the world. The idea was that understanding COVID-19’s implications for atrocity prevention could benefit from journalistic perspectives that reveal responses and impacts across different levels and sectors of society in a variety of geographical and political contexts.

Seven of those pitches were commissioned, with research and on-the-ground reporting taking place in the first several months of 2021.

This month, we published the final article in the series, completing a body of work that spans a range of topics, regions, and media formats:

- Annie Hylton explored the connections between gender-based violence and risks for atrocity crimes in the context of COVID-19 in Poland, featuring photography by Maciek Nabrdalik.

- Tatira Zwinoira investigated how COVID-19 lockdown measures in Zimbabwe may have been used to commit atrocity crimes against women, featuring photography by Tafadzwa Ufumeli.

- Jayaprakash Tissainayagam explored the ways in which Sri Lanka’s pandemic response exacerbated the vulnerabilities of minority groups, including the Tamil people and Muslim population.

- Natalia Messer reported on the experiences of Indigenous and Afro-Colombian peoples who faced increased violence throughout the Colombian government’s response to COVID-19.

- Adnan Bhat examined the impacts of restrictive laws imposed by the government of India during its COVID response in the disputed region of Kashmir, featuring videography by Syed Shahriyar.

- Caroline Tracey examined COVID-19’s contributions to increased violence against women in Mexico, featuring photography by Gabriela Esquivel.

- Braema Mathiaparanam, a former Nominated Member of Singapore’s Parliament, analyzed how risks and rights violations have increased for undocumented people in Malaysia during COVID-19.

In addition to the commissioned articles, Mark Leon Goldberg, host of the Global Dispatches Podcast, produced four podcast episodes featuring fascinating interviews with Red Flags or Resilience authors that dive deeper into their stories and takeaways from their reporting.

Commissioned journalists approached their stories using two lenses of analysis: the UN Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes and Alex Bellamy’s five factors for strengthening resilience. The journalists then pursued stories from angles of their choice based on their own research, focusing on frontline, personal perspectives in specific country contexts—sometimes collaborating with visual journalists to capture photography and video to bring their stories to life.

Pandemic as Risk Factor for Atrocity Crimes

The Framework of Analysis provides 14 risk factors that increase a society’s susceptibility to violence and various indicators that explore different manifestations of each factor. Under this framework, the COVID-19 pandemic itself can be understood as an event that has potential to generate instability or spark atrocity crimes (Indicators 1.2 and 8.9). In these journalistic pieces and analysis, authors identify additional indicators that have shifted either as a direct or indirect result of the pandemic, showing how risk factors for mass violence are manifesting in different situations.

- In stories from Mexico, Poland, and Zimbabwe, we see examples of gendered dimensions of risk, especially how violence against women can serve as a tool of terror and enable other forms of violence (Indicator 7.9).

- Other authors demonstrate patterns of discrimination against marginalized populations, including local inhabitants of Jammu and Kashmir, undocumented populations in Malaysia, Indigenous and Afro-Colombian peoples in Colombia, and the Tamil people and Muslim population of Sri Lanka. Among other indicators, these pieces highlight how government policies or a history of violence (Indicators 9.1 and 9.3) create increased risk for vulnerable populations during the pandemic.

Because this project explores how factors for risk and resilience can develop in a variety of settings, it equips policymakers and advocates to better understand the manifestations of risk. This situational awareness, in turn, can encourage better emergency response and recovery efforts that support more peaceful societies.

As Bellamy writes, all external actors—including international, regional, and local organizations—can help uphold local sources of resilience. The Red Flags or Resilience commissioned articles, featuring rich reporting, research, and images from the ground, are intended to spark continued thought and dialogue on these sources of prevention and how actors across different sectors and levels of governance can build stronger communities.