Mass Violence and Atrocities | Selected Article

The Potential of Private Enterprise

Strengthening Resilience in Southern Iraq

In August 2018, images circulated across Iraqi social media showing the southern city of Basra’s famous Shatt al-Arab waterway flowing black with pollution. The ailing freshwater lifeline, which passes through the heart of Iraq’s third-most-populous city and oil-producing nucleus, provided a striking visual depiction of the slow-churning environmental and socioeconomic ills plaguing southern Iraq today. These challenges, coupled with Baghdad’s decade-long inability to manage the effects of unemployment, displacement, and poverty on southern Iraqi communities, fueled widespread protests that roiled southern provinces throughout the summer and rattled the country’s post-2003 political system. Demonstrations presaged looming violence in southern Iraq and compounded a sense of unraveling within what many observers had considered the country’s most stable region. The Iraqi government had long taken southern Iraq for granted amid more-pressing security concerns. However, the May 2018 parliamentary elections, in which only approximately 14.4 percent of eligible Basrawi voters participated, pushed simmering anger at the region’s decay into high gear. By October 2018, policymakers had few palatable options to avoid looming violence in the region.

Baghdad today faces a critical question: how to build communities resilient to the economically and politically driven instability threatening to upend southern Iraq. Of course, economic factors are not the sole drivers of conflict in southern Iraq. Yet they point to the deeper political and governance failures—chiefly rampant corruption, environmental decay, and insufficient service provision—motivating protesters and militants. The answer to these challenges may lie with young Iraqis eager to expand outside the country’s increasingly bloated public sector. The south’s mass protests, although dangerous, also point toward new opportunities for restructuring southern Iraq’s economic and social patterns.

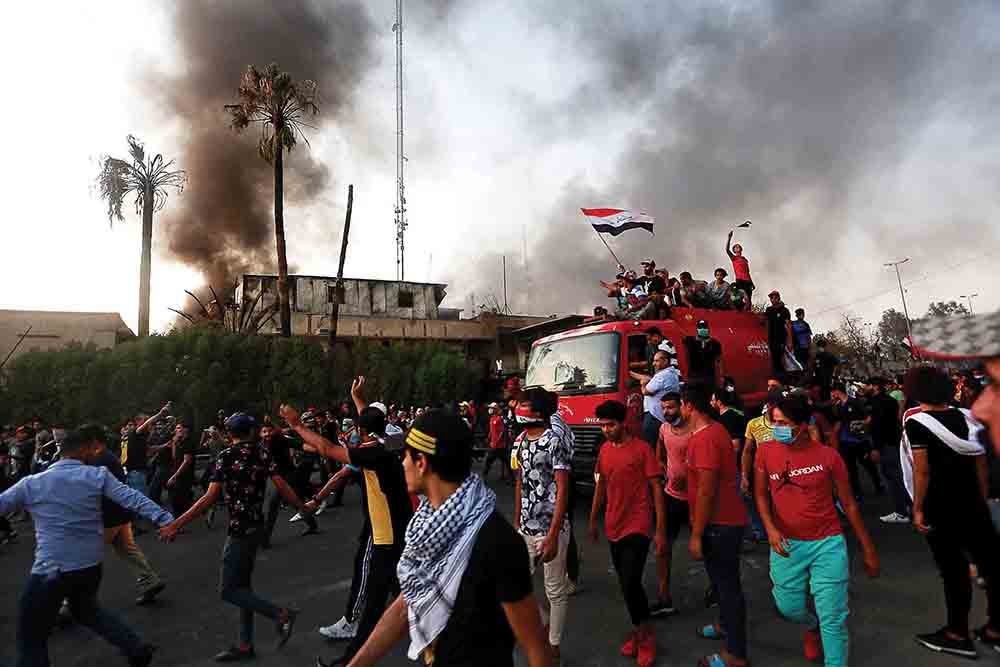

Reuters/Alaa al-Marjani

Private enterprise, emerging as a possible solution for ballooning youth unemployment and economic malaise, offers an energized young population alternatives to the violent nonstate groups that have fostered conditions for current instability. For many Basrawis, the key to future resilience lies not amid Baghdad’s stale political debates but rather in the hands of southerners eager to invest time, money, and relationships in their communities.

Threat of Violence

The protests that swept across southern and central Iraq in summer 2018 emerged partially as an outpouring of anger against Baghdad’s failure to deliver on promises of economic revitalization and development in the period following the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS). Since February, Iraqi politicians have pledged renewed support in the form of private investment and foreign capital flows to communities impacted by the four-year military campaign against ISIS. However, this summer’s water shortage, which exacerbated a worsening public health emergency and agricultural collapse, highlighted what many demonstrators believed to be the hollowness of Baghdad’s response to the south’s interrelated challenges. In late July, one student protester in Basra city explained his decision to join the protest movement thus: “The government and the politicians left us no choice but to revolt. The price of their inaction is rage. Perhaps if we shout, they’ll listen.”

Reuters/Alaa al-Marjani

His anger speaks to the drivers of instability threatening Iraq’s oil-producing heartland. Nearly 15 years after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime, southern Iraq remains without sufficient electricity, water, health care, education, or other basic services despite vast oil wealth and sustained foreign energy-sector investment. Ongoing economic challenges, including high unemployment and rising poverty, have narrowed focus among many southern communities on the deeper governance failures, fomenting increasingly vocal rejections of Baghdad’s political actors. Critically, the Iraqi government’s inability to draft legislation or policies that address such interrelated sources of instability—chiefly graft, corruption, and insufficient service provision—has pushed the region toward violence.

In 2017, for example, profit from southern Iraqi oil production and export accounted for approximately 95 percent of the country’s budget. By contrast, a UN World Food Programme survey concluded that southern Iraq’s populations would likely suffer from “widespread and severe food insecurity” by late 2018, with youth unemployment and poverty rates hovering near 30 percent. A concurrent July 2018 Iraqi government study of salinity levels in Basra’s Shatt al-Arab found water “unsafe for consumption or use in other household tasks, such as washing of clothes.” Unchecked environmental and economic decay has translated into dangerous instability as tribal militias and criminal gangs fill the government’s void with bottled water, electricity, and employment.

Massive rural emigration into Basra’s slums has aided these groups’ recruitment efforts, leaving the Iraqi and provincial governments unable to effectively administer large swaths of urban territory and economic activity in the region. Graft manifested in logistical and economic networks, as contractors were obliged to purchase supplies like cement, steel, or piping from tribal organizations at two or three times the market price. Local infrastructure projects languished for want of sufficient funding to pay both legitimate and corruption-related costs.

For example, a recent investigation from Iraq’s Integrity Commission found that 13 water desalination plants had been delivered to Basra since 2006 but were never put to use. According to sources in the Interior Ministry, the international donors had failed to pay Basrawi tribal organizations the necessary “fees” to install the equipment, prompting local administrators to loot parts and siphon installation funds to cover these demanded costs. One young protester concluded angrily: “How can we expect anyone to invest in our city if our politicians and the militias put this funding into their own pockets? Of course, I am in the street now. I have a college degree, I am ready to work for my city. But in the face of such absurdity, what other option do I have?”

Between November 2017 and April 2018, southern Iraq averaged 12 to 14 significant protests (comprising more than 150 individuals each) per month, with large-scale demonstrations concentrated around Basra, Nasiriyah, Samawah, and Rumaitha. By July, the region was experiencing at least one protest each day, with several proving fatal after security forces used live rounds to disperse demonstrators. Meanwhile, tribal- and militia-related violence intensified. In February 2018, Baghdad deployed approximately 20,000 soldiers to address a surge in militant criminal activity. By June, rates of violence had surpassed January levels across the south.

Opening Iraq for Business

The current climate of violence undermines promises of privately funded development promulgated by Baghdad since 2017, threatening to spook the investors needed to jump-start regional development. As protest and criminal activity continue, the Iraqi government’s chances of attracting sufficient foreign direct investment to lift the region from its economic malaise appear increasingly slim. Iraq’s wealthy neighbors, including Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have shown interest in southern Iraq’s investment potential. However, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have both been quick to note that corruption, insecurity, and threats from Iran-aligned militant groups could prevent participation on significant projects.

Reuters/Essam Al-Sudani

Reconciling the need for widespread economic reform with the realities of southern Iraq’s political environment is critical if the region’s leadership hopes to reverse the past year’s troubling trend toward instability. Baghdad’s original economic recovery and investment plan, which was outlined late last year through a series of ministerial workshops and white papers, sought to emphasize the country’s swiftly improving business environment. In August 2017, the Iraqi Central Bank issued its first bond in over a decade in a bid to raise $1 billion for reconstruction. Six months later, the National Investment Commission (NIC) published a list of 157 critical reconstruction and development projects, for which it sought $100 billion in foreign direct investment.

These initiatives focused on massive infrastructure restoration and economic diversification efforts, including a new freight and passenger railway from Mosul to Basra and multibillion-dollar urban metro systems in Baghdad, Basra, and Karbala. Meanwhile, the NIC also planned for the creation of four specialized economic zones in Babylon (heavy industry), Diwaniya (agriculture and agrophosphates), Ninewa (fine machining), and Baghdad (advanced cyber, information, and renewable-energy technologies), modeled on similar administrative areas in the UAE.

In the uncertainty that followed the May 2018 parliamentary elections, however, little headway has been made toward initiating these projects. According to Basra University political scientist Sajad Hussein, these plans were simply too ambitious: “Politicians focused on prestige projects, such as a new sports stadium or metro systems, while armed gangs controlled our street corners and dictated local government spending.” Instead, what southern cities like Basra needed were “local-level, dirty investments in sanitation infrastructure, road restoration, or electricity equipment that would remove the militias’ control over essential services, networks of graft, and revenue streams.” As Sajad notes, the NIC’s proposals ultimately failed to provide this framework for building an economic and infrastructure system resilient against “criminal organizations that foment long-term violence and instability as a means of ensuring short-term financial gain.”

Resilience Through Private Enterprise

Although mostly unsuccessful, Baghdad’s efforts nevertheless helped to introduce discussions regarding the country’s private and business sector potential. “It may simply be that the people of the south, through their own initiative and released potential, will prove the region’s strength against violence,” Sajad concluded. For Sajad and like-minded colleagues at Basra University, the summer’s protests sparked a surprising sense of optimism. Whereas Baghdad’s prestige-oriented reconstruction effort may have failed, demonstrations seemingly highlighted the emergence of a young population eager to strengthen communities against destabilizing elements that have fueled corruption, extortion, and violence. Promoting private enterprise and economic opportunity among this population could prove an effective way to support this goal. “Putting economic recovery in local hands means there is no more opportunity to wait,” Sajad declares.

Focus on domestic private sector growth aims to mobilize Iraq’s enormous, well-educated young population, encouraging the emergence of business incubators and collaboration spaces across the country. Approximately 60 percent of Iraqis are younger than 25, and the country has the 17th-fastest population growth rate globally; with an estimated 16.5 percent national unemployment rate (much higher for the under-25 population), the Iraqi economy has significant room for growth if reforms are sustained, partially demonstrated by a recent 11 percent increase in the country’s stock market as investors anticipate reconstruction opportunities.

Basra’s future resilience against looming violence will depend on whether young people can successfully build livelihoods outside the orbit of militant organizations. As southern men return from the battlefields against ISIS, the need for alternative sources of employment and economic stability has become increasingly pressing. Baghdad’s traditional solution, offering public sector jobs en masse, cannot manage this rising demand. As one of Sajad’s students explained, “I don’t want to fight in a gang. I don’t want a meaningless salary. I am ready to use my mind and my energy, not a Kalashnikov.”

Getty Images/Scott Peterson

However, the structural challenges facing young Iraqi entrepreneurs like him are significant. Rampant corruption hampers contract allocation and investor confidence that new business could turn a profit in the Iraqi market. Within Iraq’s public-sector-dominated business environment, political power rests with those who can provide their ministries with the most lucrative government contracts. As a result, many business owners in Iraq note that it is impossible to operate without paying exorbitant bribes, often to tribal organizations and midlevel bureaucrats in charge of facilitating contract and permissions processes. While the large oil and gas firms that dominate Iraq’s investment landscape can afford such costs, many smaller private sector investors are hard pressed to overcome these financial hurdles. To date, this system has encouraged megadevelopment projects that often go un- or half-finished while simultaneously sucking resources from smaller-scale enterprises that provide employment-boosting potential, such as manufacturing, local commerce, or retail.

Overcoming these obstacles to build a resilient southern Iraqi economy will require cooperation between government and private sectors. Baghdad can support youth engagement by enacting regulatory and banking-sector reforms, making it easier for Iraqis to acquire capital domestically, build partnerships with foreign entities, and maneuver the country’s overwhelming bureaucracy. For example, a nondiscrimination principle announced in a February 2018 NIC memo that provides a mechanism for domestic and foreign companies to raise business-related grievances will help link international capital to Iraqi talent. A new online reconstruction database introduced in early 2018 further reinforces investor confidence by addressing widespread corruption within Iraq’s ministries. Meanwhile, a $2 million United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) economic diversification effort scheduled to run through 2019 aims to match international management experts with specific Iraqi ministries in order to build internal asset recovery mechanisms, identify financial assets located outside Iraq, and, ultimately, reduce opportunities for graft. Encouragingly, just one year after launching this program, the UNDP reports a 5 percent reduction of financial waste within targeted Iraqi government offices.

Reuters/Essam Al-Sudani

Ultimately, privately fueled economic development alone cannot solve the region’s interrelated economic, political, and environmental dilemmas. Resilience must instead emerge from cooperation between a reform-minded, flexible government and the investors such policymakers hope to attract. The Iraqi market holds incredible growth potential in terms of physical investment opportunities and human capital. It is the Iraqi government’s responsibility to create an environment in which private investment, industry, and entrepreneurship can take root. Economic reforms focused on private sector development could reinvigorate the south’s ailing regulatory frameworks, providing a safety valve against looming violence and mobilizing an energetic young population eager to invest in the region’s future. Troublingly, the Iraqi government has yet to fully embrace this crucial policy role. Instead, political actors have resorted to immediate bureaucratic solutions to the long-term sources of instability. As southern protests intensified in June and July, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi announced a plan to create 10,000 new public service and civil service jobs, ostensibly from thin air. Within days, southern ministries received more than 50,000 resumes from young applicants.

However, for some observers, the overwhelming number of submissions signaled a potential source of optimism that Iraqi political actors would be wise to recognize. “The politicians face a simple choice,” Sajad declares with a smile. “They must decide whether to feign helplessness or to harness the tireless optimism of the Iraqi people in building their country’s peaceful and prosperous future.”

Matthew Schweitzer is a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC, where he focuses on Iraq and Persian Gulf security. This article includes excerpts from his work that previously appeared in the Global Observatory and the Education for Peace in Iraq Center.

The Stanley Center’s efforts in mass violence and atrocity prevention consider how all actors, including the private sector, can effectively engage and collaborate to promote societies resilient to violent conflict. The foundation’s current work focuses on using evidence to inform policy action at national, regional, and global levels to create peace and prevent the worst forms of violence.

Related Publications

Mass Violence and Atrocities

Systemic Racism in Mass Violence and Atrocity PreventionMass Violence and Atrocities

Assessing Our Strategic Priorities for Mass Violence and Atrocity PreventionMass Violence and Atrocities

The Escalating Risk of Mass Violence in the United StatesRelated Events

May 6, 2024

The City Key: Unlocking Solutions to Identity-based Violence – Policy Salon Dinner and WorkshopFebruary 8, 2024

Lessons for and from Effective Offices of Violence PreventionSeptember 12-13, 2022

Peace in Our Cities: Closing Summit for 17 Rooms